PDF download.

Slime Molds – Social Amoebae

In this document I make the case for keeping slime molds in the future

Biolab in Calafou, and outline my perspective on them.

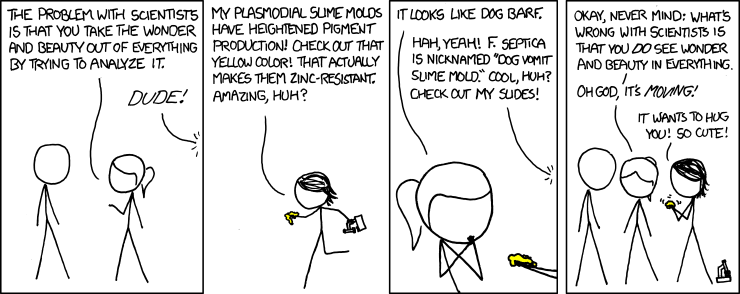

Slime molds raised to attention in the last years, mainly since the turn

of the century, and went viral with videos such as

this and

this. They were even

featured in XKCD, the acme

of geek fame. They have interesting properties that warrant scientific

attention and they are simple enough to study without an expensive

laboratory.

Why slime molds are awesome?

- They are the most intelligent brainless creatures!

- They can be used to build computers – OK, at least logic gates. :)

- They calculate shortest routes and build networks.

- They are one of the first organisms which lived on land.

- They are not animals, plants or mushrooms.

- They sport funny shapes and colours.

What can be done (in Calafou) with slime molds?

- We can keep them safely in petri dishes, etc.

- We can build mazes, make stop motion photos and show to visitors.

- We can make software to recognise and track slime molds on images.

- We can reproduce experiments done in prestigious universities.

- We may make mazes with 3d printers for them algorithmically.

- We might develop neural networks which simulate their behaviour.

- We might develop software which builds mazes for specific problems.

- We might collaborate with the

HAROSA

research network to solve logistics problems with them.

Notably, according to

some

sources

they can be interesting for measuring metal toxicity and even for

biological reclamation of heavy metal contamination, especially zinc,

etc. This can be potentially relevant for dealing with the contamination

of the Anoia river. Even if we cannot save the river this way, it may be

possible to contribute to scientific research by making and documenting

some experiments.

How can we get some slime molds?

There are three ways to get slime molds:

- buying them in

kits,

- getting them from somebody who has them,

- or harvesting them from the forest.

The last option seems good but there seems to be a lack of documentation

on how to do it. The second option could work if we make some more

research online, find the right people and ask them. However, for a

start, the first option is the most straightforward. I can invest in

ordering a few different kits and we can see where to go on from there.

In addition to the slime molds themselves, the rest of the necessary

equipment is trivial. Most howtos suggest oat meal flakes to feed them

and petri dishes to keep them. They do have a complex life cycle, but at

the moment I am not aware of any difficulties with keeping them alive

and multiplying for an extended period of time.

My motivation and research programme

As it will quickly become apparent, my interest in slime molds is bound

up with my interest in the ideological and historical issues of

cybernetics, and it is largely theoretical.

Slime molds embody several large scale changes in society and technology

which I study from the perspective of a critical history of ideas. They

stand at the intersection where metaphors are operationalised and

translated from one realm of reality to another (an ontological shift):

- Networks: networked creatures – master metaphor for everything?

- Computers: biological computers – computation as phenomena?

- Societies: social amoebae – the social body?

Networks: How a simulation replaced reality

At the same time as computers really happened, i.e. when the von Neumann

Architecture – which defines a computer as the combination of a (a)

processing unit, (b) a storage device and (c) a memory between the two –

crystallised (von Neumann 1945), neural networks – an alternative

computing paradigm – were being developed by McCulloch and Pitts (1943),

and successfully implemented by (1958). Even the founding father of

cybernetics, the mathematician Norbert Wiener, developed a similar model

during the same period, in cooperation with the Mexican physician and

physiologist Arturo Rosenblueth (Wiener and Rosenblueth 1946). These

people were all adepts of cybernetics, an ambitious research program

which originally aimed at building a functional model of the brain.

(Pickering 2010) Cyberneticians abstracted away the biological qualities

of living organisms (especially the brain) in exchange for a

mechanistic, calculative model – an approach that quickly turned into an

avant-garde scientific paradigm, redefining in those logico-mechanistic

terms such categories as life, purpose, reason and subjectivity. (Dupuy

2000) Therefore, from base research in the hard sciences, in a few

decades it became an ontological-metaphysical project, the effective

deployment of an ideology through the whole territory of social life.

(Tiqqun 2012)

To summarise, the key movement was comprised of two parts: first, the

abstraction of biological phenomena into a logico-mechanistic model; and

second, its reification from model to the very blueprint of reality. The

idea of networks in particular was drawn from the image of the

interconnected neurons in the brain, which was turned into an abstract

logical model, and finally reified to nothing less than an actual law of

nature. The idea of the network is thus interesting for its intellectual

trajectory from an observed biological phenomena through a scientific

model which aimed at understanding it to a concrete metaphor treated as

the nature of almost everything: a veritable ideal.

A principal example of how cybernetics shaped the intellectual history

of the second part of the twentieth century is Actor Network Theory, a

sociological research program developed by Bruno Latour primarily in the

1990s. (Latour 1993; Latour 1996; Latour 2005) At the moment the

hegemonic theoretical framework in the sociology of technology, it

presents itself as a “practical metaphysics” (Latour 2005, 50f),

granting equal attention and equal powers to both human and non-human

entities. The network of actors is the principal metaphor of its

sociological imagination. While it seeks to give an impartial account of

how networks are formed, function or fail, its ontological operation

restricts everything that exists – and can exist – in reality to these

same networks. If analytically actors are considered black boxes,

ultimately they too can be decomposed into networks. Thus nothing else

can exist in the world but networks – everything else proves to be an

illusion.

Of course the power of networks does not stop at the level of

intellectual reflection. We do not simply understand the world this or

that way – we also act based on such and such an understanding. When

everything can be seen as a network of networks, everything has to be

reorganised to become a network of networks. Communication

infrastructures, computer architectures, the global firms of capital,

its markets and the geopolitical strategies of imperialist nation states

– in conjunction with the very social movements which oppose them.

Humans start to live in the context of social networks and networking

becomes the principal professional activity, while liberal capitalism is

rebuilt according to The Wealth of Networks (Benkler 2006) (a book

playing on the title of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations). In Manuel

Castells’ The Network Society, nothing else is allowed to live but

networks. When all problems are posed in the categories of network

ontology, all solutions are posed as network ontologies. Being a network

becomes the ultimate recipe for success – since everything else is just

a badly functioning network anyway.

The moral of the story is that cyberneticians started working on a model

which would correspond to reality more than the models before, and ended

up with a reality which has to correspond to its own models more than

before.

Obviously, slime mold research touches upon many of the issues outlined

above. Slime molds are living biological organisms which (are made to)

look and act like a network, and in turn used to model other networks in

the real world, with the idea of eventually generating a system which

can compute these networks on a logical level. The foundational notion

of slime mold research is that there is no ontological difference

between biological networks and logical networks, or any other networks

such as transportation infrastructures like railroads, the interaction

of the neurons in the brain, the collective behaviour of certain animal

populations, etc.

“In the province of connected minds, what the network believes to be

true, either is true or becomes true within certain limits to be found

experientially and experimentally.” – John Lilly, The Human

Biocomputer (1974)

Computing: Happens in the Brain, in Nature, and in Machines

As Dupuy (2000) explains, computers were not the material inspiration

for the cybernetic conception of the brain. In fact the cybernetic

conception of the brain was formulated before, and computers came to be

the material expression of it. However, in the history of cybernetics

there were many other research directions open. Thanks to the

organisation of cybernetics as a general science, and the involvement of

a high number of physicians in the movement (on both sides of the

Atlantic), especially biology, logics and computing were highly related.

Let me recount a few examples. Stafford Beer was one of the three

fathers of cybernetics in the United Kingdom (along with Ross Ashby and

Grey Walter). His life trajectory – from the chief consultant to the

British Steel Industry, through the architect of the Cybersyn project to

reorganise the economy of Allende’s Chile to yoga guru – could itself

fill a novel. His first forays into cybernetics, however, had to do with

biological computers. In fact not even biological computers. He was

firmly against computers. He was saying that it is really stupid and

selfish to build sophisticated machines that can count. Such a mistake

derives from the hubris of humanity, that we go around thinking that we

are the only creatures that can think. But every living organism is a

complex ecosystem which balances its inputs and outputs according to

well defined requirements: the requirements of its environment.

Therefore, we just have to look around and find the ecosystem we need

for our calculations.

In line with his ideas, he proposed to replace the management of steel factories with… a pond. The pond would do the calculations necessary to run the factory better than the human management. The main difficulty in this endeavour was bridging the gap between humans and natural ecosystems: how to do input and output? His best idea for input was saturating the pond water with steel powder, and using magnetic fields to give instructions to the ecosystem. However, as much as natural ecosystems automatically tend towards equilibrium, most of them cannot strive against a high concentration of metals – so soon everything died in his pond. [*]

His second idea was a living tissue arranged in a film which was pierced

at intervals with electric wires. He noticed that once the wires are in

place, paths form connecting the wires. Beer concluded that it was

evidently an example of adaptation, and eventually communication between

the human and the organism. Soon he prophetised that if confronted by

noise, the organism will develop an ear. In order to test his theory at

some point he was holding out the poor creature of his living room

window, so that it would pick up the noise of the passing cars in the

street. This second idea was not more successful then the first one.

However, Beer had good reasons to concentrate on biological computing

and therefore he refused the help offered by Alan Turing several times.

Turing was building a pioneering mainframe computer at the time, and

thought that the calculations Beer had in mind could be run as

simulations on the new machine. Towards the end of his life, Beer

returned to the idea of the biological computer and wrote a book –

accompanied by photographs of Hans Blohm – admiring the computing

capacity of the Atlantic ocean. (Beer 1986)

On the other side of the Atlantic, a hotbed of cybernetics, – in fact

virtually the only serious institution explicitly devoted to cybernetics

– has been the Biological Computer Laboratory, founded in 1958 by Heinz

von Foerster. Many key cyberneticians were visiting scholars there. For

instance the aforementioned ideas of McCulloch and Pitts were worked out

in that milieu. (Müller 2007) Inspired by the Mexican physician Arturo

Rosenblueth (Rosenblueth, Wiener, and Bigelow 1943) and the Chilean

biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela (Maturana and Varela

1980 [1972]), they believed that certain problems cannot be solved by

mere calculating machines like computers. However, they held on to the

idea that thinking is a logical operation which can be implemented in

various media, be it biological material, mechanics or electronics. The

first step in the realisation of this thesis was created by the

engineering student Paul Weston. His contraption, the Numarete, could

recognise the number of objects (or rather, shadows) placed in front of

it. According to Müller, “The Numarete was a computer that was not built

according to the (reductionistic) von Neumann architecture, but rather

was in a sense ’oblique’ to this architecture: it was based on the

parallel operations of its modules.” It was a custom-built electronic

box operating according to the principles of the aforementioned neural

networks. The whole laboratory draw its inspiration from the idea that

it is possible to build machines with capabilities of living creatures,

and the way to do it is following the logical operation of observed

natural phenomena.

Interestingly, the current epicentre of slime mold research is a very

similar institution, the International Center of Unconventional

Computing in Bristol, operated by the University of the West of England,

where its mastermind Andrew Adamatzky is building the slime mould

computers (Adamatzky 2010). The academic study biological computers

became virtually extinct following the spectacular success of the von

Neumann architecture, and even the development of neural networks was

put on hold for more than a decade after the publication of a book by

the adherents of the rival school of symbolic artificial intelligence

(Minsky and Papert 1969). As a result, bionicians around the turn of the

millennium picked up the threads close to the point where the

cyberneticians left them off. What changed, however, is the scientific

climate which is not ideal for base research any more, so that novel

efforts are not couched in the same level of epistemic-contextual

reflection as before, but more narrowly focused on narrow practical

applications. While some of the avant-garde idealism which drive

cybernetics withered away, many of the dangerous assumptions behind such

work continue to linger on without a critical evaluation. Such critique

is only possible from a perspective where two disjunct lines of inquiry

meet: the history of ideas conducted with a hermeneutics of doubt, and

the sympathetic anthropological field work which appreciates the

complexities of contemporary scientific practice.

Societies: Social Laws from Natural Phenomena, and Back

Natural laws as observed in biological phenomena often inspired and even

underpinned political thought. Hobbes’ Leviathan as the philosophical

imagery of the society as a unified social body is perhaps the most well

established example. The discoveries of cybernetics have not been an

exception. A logical order which can be abstracted from the behaviour of

living organisms and which applies in a more – or less – metaphorical

way to the world of human social affairs is a recurring theme in the

history of ideas.

The idea of autopoiesis and the related concept of self-organisation and

autonomy, (Maturana and Varela 1980 [1972]) as well as the idea of

ecosystems that tend towards equilibrium through negative feedback,

developed by cyberneticians, have been absorbed by the older tradition

of anarchist collective organising, mainly as conceptual metaphors.

(Curtis 2011) Anarchist ideologies depended for long on a positive

anthropology which asserted that people are generally good, but their

positive natural tendencies are short-circuited by the social conditions

in an authoritarian society (Newman 2007 [2001]). The corollary is that

when authoritarianism is not enforced by social structures, people start

to act in a more positive way, described in the language of solidarity,

mutual cooperation, and so on. (Graeber 2004) Anarchists found support

for these propositions in the scientific results stated above. Moreover,

another branch of cybernetics have also inspired anarchist theory and

practice in a similar way, namely chaos theory and emergence. Chaos

theory provided support for the idea that the actions of a small

minority (or perhaps even an individual) can have far-ranging structural

effects on society as a whole. On the other hand, emergence supported

the claim that horizontal social order rises up naturally wherever

people are left to organise themselves in the absence of oppressive

authoritarian institutions like the state. Interestingly, these

scientific trajectories have been developed most convincingly in the

area of emergent evolutionary theories, which stated that evolutionary

chains tended towards complexity and exhibited signs of spontaneous

self-organisation – therefore refuting or at least complementing the

idea of natural selection as the engine of biological history. (Wolfram

2002) These results are evidently useful in countering vulgar

interpretations of socio-darwinism which take the “survival of the

fittest” as their slogan.

Slime moulds entered this discussion once it has been realised that

while they live their life mostly as single-cell organisms, when they

face difficult environmental conditions such as the lack of nutrients,

they flock and form a single organism, joining their cells into a single

body. Recent results dubbed some species “social amoebae” – claiming

that they actually form a society of the species comparable to an ant

farm or a beehive. Since these animals have long been the subject of

study inspiring social theories, such a line of inquiry opened up,

offering great possibilities for ideological manipulation and

misinterpretation. Interestingly, the first discoveries suggested that

perhaps in contrast with ants and bees, there is “competition” and

“cheating” between certain amoebae when the cells which meet to form a

body have different genetic identity and materials. In these articles,

the language usually applied to the analysis of society is transferred

and applied to the understanding of micro-organisms. Observe the

following sample from the abstract of a recent article on slime moulds:

Altruism and social cheating in the social amoeba Dictyostelium

discoideum

The social amoeba, Dictyostelium discoideum, is widely used as a simple

model organism for multicellular development, but its multicellular

fruiting stage is really a society. Most of the time, D. discoideum

lives as haploid, free-living, amoeboid cells that divide asexually.

When starved, 104–105 of these cells aggregate into a slug. The anterior

20% of the slug altruistically differentiates into a non-viable stalk,

supporting the remaining cells, most of which become viable spores. If

aggregating cells come from multiple clones, there should be selection

for clones to exploit other clones by contributing less than their

proportional share to the sterile stalk. Here we use microsatellite

markers to show that different clones collected from a field population

readily mix to form chimaeras. Half of the chimaeric mixtures show a

clear cheater and victim. Thus, unlike the clonal and highly

cooperative development of most multicellular organisms, the development

of D. discoideum is partly competitive, with conflicts of interests

among cells. These conflicts complicate the use of D. discoideum as a

model for some aspects of development, but they make it highly

attractive as a model system for social evolution. (Strassmann, Zhu,

and Queller 2000)

Methodology

While I am reading about theories and theorists, experiments and

scientists, and so on and so forth, I’d like to try out these drifts of

the imagination in which you get entangled when you engage concretely

and practically with such creatures, experiments and phenomena. Beyond

merely reading the documentation about how ideas developed, what about

trying to recreate the existential and epistemological conditions which

moved such developments? I believe that certain experiences have

transformative have transformative power, and that a milieu can only be

grasped properly through developing some actual contributions to it,

however modest they may be.

maxigas, 2013-08-28→2013-09-02, Budapest

Notes

[*] It is interesting that slime mold research even touches upon this difficulty, albeit slightly. Note the section above on the resistance of slime molds to high concentration of metals. Additionally, there are even aquatic slime molds. Maybe Stafford Beer could go on with his experiment if he used slime molds.

References

Adamatzky, Andrew. 2010. Physarum Machines: Computers from Slime

Mould. Toh Tuck Link: World Scientific.

Beer, Stafford. 1986. Pebbles to Computer: The Thread. Toronto: Oxford

University Press.

Benkler, Yochai. 2006. The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production

Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Curtis, Adam. 2011. “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace.”

documentary series.

Dupuy, Jean-Pierre. 2000. The Mechanization of the Mind: On the Origins

of Cognitive Science. Princeton, NJ and Oxford: Princeton University

Press.

Graeber, David. 2004. Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Chicago:

Prickly Paradigm Press.

Latour, Bruno. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

———. 1996. ARAMIS of the Love of Technology. Cambridge, MA and London:

Harvard University Press.

———. 2005. Reassembling the Social. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lilly, John C. 1974. The Human Biocomputer. New York: Bantam Books.

Maturana, Humberto, and Francisco Varela. 1980 [1972]. Autopoiesis and

Cognition: The Realization of the Living. Dordrecht, London, Boston: D.

Reidel.

McCulloch, Warren, and Walter Pitts. 1943. “A Logical Calculus of Ideas

Immanent in Nervous Activity.” Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 5

(4): 115–133.

Minsky, Marvin, and Seymour A. Papert. 1969. Perceptrons: An

Introduction to Computational Geometry. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Müller, Albert. 2007. “A Brief History of the BCL: Heinz Von Foerster

and the Biological Computer Laboratory.” In An Unfinished Revolution?:

Heinz Von Foerster and the Biological Computer Laboratory (BCL),

1958–1976, ed. Albert Müller and Karl Müller. Vienna: Edition Echoraum.

von Neumann, John. 1945. First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC.

Philadelphia, PA: Report for the United States Army Ondnance Department

and the University of Pennsylvania.

Newman, Saul. 2007 [2001]. From Bakunin to Lacan: Anti-Authoritarianism

and the Dislocation of Power. Plymouth: Lexington Books.

Pickering, Andrew. 2010. The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another

Future. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Rosenblatt, Frank. 1958. “The Perceptron: A Probalistic Model For

Information Storage And Organization In The Brain.” Psychological

Review 65 (6): 386–408.

doi:10.1037/h0042519.

Rosenblueth, Arturo, Norbert Wiener, and Julian Bigelow. 1943.

“Behavior, Purpose and Teleology.” Philosophy of Science 10 (1):

18–24.

Strassmann, Joan E., Yong Zhu, and David C. Queller. 2000. “Altruism and

Social Cheating in the Social Amoeba Dictyostelium Discoideum.” Nature

(408) (December): 965–967.

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v408/n6815/pdf/408965a0.pdf.

Tiqqun. 2012. The Cybernetic Hypothesis. The Anarchist Library.

http://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/tiqqun-the-cybernetic-hypothesis.

Wiener, Norbert, and Arturo Rosenblueth. 1946. “The Mathematical

Formulation of the Problem of Conduction of Impulses in a Network of

Connected Excitable Elements, Specifically in Cardiac Muscle.” Arch.

Inst. Cardiol. (16): 205.

Wolfram, Stephen. 2002. A New Kind of Science. Champaign, IL: Wolfram

Media.